How do banks make money?

To most people, a bank is just a safe place to keep money or a place to go when you need a loan. We see their marble lobbies, their logos on stadiums, and their apps on our phones. They seem like a permanent, immovable part of our economy.

But have you ever stopped to ask a simple question: How do banks actually make money?

They don’t charge most of us just to hold our cash in a checking account. In fact, they sometimes even pay us a tiny bit of interest for a savings account. Yet, major banks are some of the most profitable corporations on Earth.

The answer is that banks are not storage facilities; they are complex, high-volume businesses. They have a surprisingly diverse number of ways to generate revenue, from centuries-old practices to modern, high-tech financial wizardry. This guide will break down every single way banks turn a profit, in simple terms anyone can understand.

The Core of Banking: What is Net Interest Margin?

If you remember only one concept, make it this one: Net Interest Margin (NIM). This is the oldest and most fundamental way a bank makes money.

In short, a bank makes money by paying a low interest rate on the money it takes in (deposits) and charging a higher interest rate on the money it lends out (loans).

The difference between those two rates is the “spread” or “margin,” and it’s the bank’s core profit.

Think of it like this:

- You Deposit: You and thousands of other people deposit your paychecks into checking and savings accounts. The bank might pay you 1% APY on your savings account. This 1% is a cost to the bank.

- The Bank Lends: The bank then takes that pool of money and lends it to other customers. They might issue a 30-year mortgage at 7% interest, an auto loan at 8% interest, or a business loan at 10% interest. This is revenue for the bank.

- The Profit: The bank’s profit is the 6% to 9% difference between the interest it pays you and the interest it earns from borrowers.

When you multiply this spread across billions or even trillions of dollars in assets, you have an incredibly powerful profit engine. This single concept, the Net Interest Margin, is the foundation of traditional retail and commercial banking.

A Deeper Look: The Two Main Ways Banks Generate Revenue

While the NIM is the classic model, it’s not the whole story. In the modern economy, a bank’s revenue is broadly split into two main categories.

- Interest Income: Money made from the interest rate spread on loans (what we just discussed).

- Non-Interest Income: Money made from everything else. This includes fees, services, penalties, and investment activities.

For decades, interest income was king. But in recent years, especially during periods of low interest rates, non-interest income has become just as crucial to a bank’s bottom line. Let’s explore both in detail.

Revenue Stream 1: Net Interest Income (The Classic Model)

This is the profit from a bank’s primary job: acting as a financial intermediary. They gather capital (deposits) and deploy that capital (loans).

The main products that generate interest income are:

- Mortgages (Home Loans): Often the largest asset on a bank’s books. A 30-year loan provides a reliable, long-term stream of interest payments.

- Auto Loans: Shorter-term loans but with typically higher interest rates than mortgages.

- Personal Loans: Often unsecured (not backed by an asset like a car or house), so they carry some of the highest interest rates for consumers.

- Credit Card Balances: When customers don’t pay their bill in full, the bank charges a high Annual Percentage Rate (APR) on the revolving balance.

- Commercial Loans: Lending to small businesses and large corporations for operations, expansion, or real estate.

- Interbank Lending: Banks even lend money to each other overnight to meet regulatory requirements, earning interest in the process (this is tied to the “Fed Funds Rate”).

How Fractional Reserve Banking Supercharges Profits

Here’s where it gets even more interesting. You might think that if a bank has $1 million in deposits, it can only lend out $1 million. That’s incorrect.

We operate under a fractional reserve banking system.

This system, managed by the Federal Reserve, only requires banks to keep a small fraction of their customer deposits on hand (the “reserve requirement”). For example, let’s say the reserve requirement is 10%.

- You deposit $1,000 in Bank A.

- Bank A must keep 10% ($100) in reserve.

- It can now lend out the other $900.

- The borrower who gets that $900 uses it to buy something, and the seller deposits that $900 into Bank B.

- Bank B must keep 10% ($90) in reserve.

- It can now lend out the other $810.

This cycle continues, effectively “creating” new money in the economy. The original $1,000 deposit can end up supporting up to $10,000 in total new money (loans and deposits).

Why does this matter for bank profits? Because it allows the bank to make far more loans than the total cash it has in its vaults. Each of those “new” loans is a new stream of interest income, all stemming from that initial deposit. It’s a powerful multiplier for their core business.

The Impact of the Federal Reserve on Bank Profits

You often hear on the news that “The Fed raised interest rates.” This has a direct and massive impact on bank profitability.

The “rate” the Fed raises is the Federal Funds Rate—the rate at which banks lend to each other. This rate serves as a benchmark for almost all other interest rates in the economy.

- When the Fed raises rates: Banks can almost immediately charge more for new variable-rate loans (like credit cards and business loans). However, the interest they pay you on your savings account usually rises much more slowly. This widens their Net Interest Margin, and profits often go up.

- When the Fed lowers rates: The opposite happens. The interest they earn on loans drops, but the rate they pay on deposits can’t go much lower (often, it’s already near zero). This squeezes their margin, and they must rely more heavily on non-interest income.

Revenue Stream 2: Non-Interest Income (The Fee Economy)

This category is everything except interest. It’s the fees, penalties, and service charges that banks collect. For many large “too big to fail” banks, this “fee income” can account for nearly half of their total revenue.

This income is so valuable because it’s not dependent on interest rates or the lending market. It’s a steady, predictable stream of cash.

Breaking Down Common Bank Fees You Pay

You’ve likely encountered many of these. They are pure profit for the bank, as the service costs them very little to provide.

- Monthly Maintenance Fees: A flat monthly fee just for having a checking or savings account, often waived if you maintain a certain minimum balance or have direct deposit.

- Overdraft Fees: A massive revenue generator. If you spend more than you have in your checking account, the bank covers the transaction (or not) and charges you a steep penalty, typically $30-$35 per transaction.

- Non-Sufficient Funds (NSF) Fees: Similar to an overdraft, but this is the fee for a “bounced check” or a declined electronic payment.

- ATM Fees: Using an ATM that isn’t owned by your bank. Your bank may charge you a fee ($2-$3) and the ATM owner will also charge you a fee ($3-$5).

- Foreign Transaction Fees: A percentage (usually 1-3%) charged on any purchase you make in a foreign currency.

- Wire Transfer Fees: Charging a significant fee ($15-$50) to send money electronically, especially internationally.

- Account Closing Fees: A penalty for closing an account that was only recently opened.

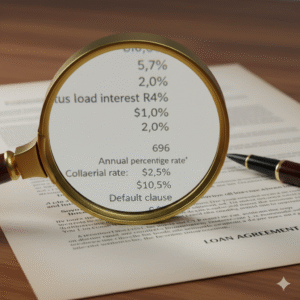

- Loan Origination Fees: A fee charged on a mortgage or business loan just for processing the application and paperwork. This is often “1 point,” or 1% of the total loan amount.

- Late Payment Fees: A penalty for missing a payment due date on a loan, mortgage, or credit card.

- Safe Deposit Box Fees: Renting a secure box in the bank’s vault.

The Credit Card Powerhouse: A Bank Within a Bank

Credit cards are such a massive source of profit that they deserve their own section. They generate revenue in multiple ways at once.

- Interest on Revolving Balances (APR): This is the most obvious one. Any customer who doesn’t pay their bill in full at the end of the month is charged a very high APR (often 18% to 29% or more) on the remaining balance. This is high-margin interest income.

- Interchange Fees (The Hidden Giant): This is the most important one. Every single time you swipe, tap, or insert your credit card, the merchant (the store, restaurant, or gas station) has to pay a “merchant fee” or “interchange fee.” This fee is typically 1.5% to 3.5% of your total purchase. That fee is then split between the card network (Visa, Mastercard) and the bank that issued your card. The bank gets a piece of every single transaction, whether you pay your bill in full or not.

- Annual Fees: Many premium and rewards cards charge an annual fee ($95 to $695+) just for the privilege of holding the card. This is pure non-interest income.

- Other Card-Specific Fees: This includes balance transfer fees (a 3-5% fee to move a balance from another card), cash advance fees (a high fee and a high interest rate for pulling cash from an ATM), and late payment fees.

The “Big Money”: How Investment Banks Earn Their Keep

So far, we’ve mostly discussed retail banking (your local branch) and commercial banking (lending to businesses). But the largest banks—like JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley—are also investment banks.

This is a different, much higher-stakes business. They don’t make their money from $35 overdraft fees. They make it in a few key ways:

- Underwriting: When a company wants to “go public” (sell stock for the first time in an IPO) or issue bonds, it hires an investment bank. The bank acts as the middleman. It buys all the shares from the company at a set price and then sells those shares to the public (like pension funds and individual investors) at a slightly higher price. The spread on that sale, multiplied by millions of shares, can be worth hundreds of millions of dollars for a single deal.

- Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A) Advisory: When one giant company wants to buy another, it hires an investment bank to be its advisor. The bank helps negotiate the price, structure the deal, and handle the complex financing. For this service, they charge an “advisory fee” that is a percentage of the total deal value. For a $50 billion merger, this fee can be enormous.

- Trading (Proprietary Trading & Market Making): Investment banks have massive trading floors where they buy and sell stocks, bonds, currencies, and complex financial products (derivatives).

- Market Making: They provide liquidity to the market. They will simultaneously offer to buy a stock at $10.00 (the “bid”) and sell it at $10.01 (the “ask”). They make a tiny profit of one cent on every trade (the “bid-ask spread”), but they do this billions of times a day.

- Proprietary Trading: This is when the bank uses its own money to make speculative bets on which way the market will go. It’s high-risk, high-reward.

Wealth Management and Asset Management (AUM)

Another major division of large banks is managing money for wealthy individuals and institutions.

- Wealth Management / Private Banking: This division caters to high-net-worth individuals. They provide a suite of services: investment advice, financial planning, estate planning, and exclusive banking perks. They earn fees for this personalized advice.

- Asset Management: The bank creates and manages its own mutual funds, ETFs (Exchange-Traded Funds), and hedge funds. They then sell shares in these funds to the public and to their wealth management clients. Their profit comes from the Assets Under Management (AUM) fee (also called an “expense ratio”), which is a small percentage (e.g., 0.5% to 2%) of the total money in the fund, charged every single year.

If a bank manages a $100 billion mutual fund with a 1% expense ratio, that’s $1 billion in pure, predictable revenue every year.

What Are the Risks? How Banks Can Lose Money

This explanation wouldn’t be complete without mentioning that this business is not risk-free. A bank’s business model is built on “leverage” (using deposits and borrowed money), and if their bets go wrong, they can fail spectacularly.

- Credit Risk: The biggest risk. This is the risk that borrowers will default on their loans and not pay the bank back. This is what happened on a massive scale during the 2008 financial crisis with subprime mortgages. If loan losses are higher than the interest income, the bank loses money.

- Liquidity Risk: This is the risk of a “bank run.” A bank’s assets (loans) are long-term, but its liabilities (your checking account) are short-term. If too many depositors demand their cash all at once, the bank won’t have it on hand, as it’s all been lent out. This is what caused the failure of Silicon Valley Bank in 2023.

- Interest Rate Risk: The risk that rates will move in an unfavorable way. If a bank has all its money tied up in 30-year mortgages at a low 3% rate, and new interest rates shoot up to 7%, it’s stuck earning a below-market rate. It will also have to pay more to depositors to stop them from moving their cash, crushing their Net Interest Margin.

- Market Risk: The risk that the bank’s own investments in stocks and bonds (its proprietary trading) will lose value.

How to Use This Knowledge: What This Means for You

Understanding how banks make money transforms you from a simple customer into an informed consumer. You can now use their business model to your advantage.

- Avoid Fees: Banks rely on you not reading the fine print. Knowing that fees are pure profit, you should actively seek out banks (often online banks or credit unions) that have no monthly fees, no minimums, and ATM fee reimbursements.

- Minimize Your Interest Payments: A bank’s biggest profit (NIM) is your biggest cost. Your goal is to pay them as little interest as possible. Pay your credit card balance in full every month. Improve your credit score to qualify for the lowest possible interest rates on your mortgage and auto loans.

- Maximize Your Interest Earnings: On the flip side, make the bank pay you. Don’t let cash sit in a 0.01% checking account. Move your emergency fund to a high-yield savings account (HYSA) or a money market fund, where you can earn a competitive rate that is closer to what the bank itself is earning.

- Understand the “Rewards”: When a credit card offers you 2% cash back, it’s not out of kindness. They are doing it to encourage you to use their card, so they can collect the 3% interchange fee from the merchant and hope you’ll eventually carry a balance and pay 25% APR.

The Bank as a Business

Banks are not your financial partner, and they are not a public service. They are a for-profit business, just like a grocery store or a car company. Their product isn’t milk or steel; their product is money.

They “buy” money from depositors at a low price (low interest) and “sell” it to borrowers at a high price (high interest). They “rent” you access to your money through services and charge fees for the convenience. And they invest their capital and yours to generate returns.

By demystifying their business model, you can make smarter financial decisions, avoid unnecessary costs, and build a better financial future.