What is an IPO?

You’ve probably seen the headlines: a hot new tech company is “going public,” and its stock price soars 50% on the first day of trading. News anchors celebrate, and the company’s founders are instantly minted as billionaires. This massive, wealth-creating event is known as an IPO.

From Silicon Valley darlings like Facebook (now Meta) and Google (now Alphabet) to recent market-shakers, the IPO is a rite of passage. It’s the moment a private company steps onto the global stage and invites the public to buy a piece of its future.

But what is an IPO, really? How does a company go from a private start-up to a publicly-traded stock on the NYSE or NASDAQ? Why do they even do it? And most importantly, what does it mean for you as an investor?

This comprehensive guide will demystify the entire IPO process, from the backroom deals on Wall Street to the trading ticker on your screen.

What Does “IPO” Actually Stand For?

Let’s start with the basics. IPO is an acronym for Initial Public Offering.

- Initial: It’s the very first time this is happening.

- Public: The company is inviting the general public (that means you, hedge funds, 401(k) managers, etc.) to become owners.

- Offering: The company is “offering” shares (small pieces of ownership) for sale.

Before an IPO, a company is “private.” Ownership is held by a small group of people: the founders, early employees, and venture capitalists (investors who fund start-ups). You can’t just log into your brokerage account and buy shares of a private company.

An IPO is the grand transition. It’s the process of selling a portion of that private company to the public, at which point its shares become listed on a major stock exchange, like the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) or the NASDAQ. After the IPO, anyone can buy or sell the stock.

Why Do Companies Go Public? The Main Motivations

Why would a successful private company want to go through the incredibly complex, expensive, and stressful process of an IPO? It all comes down to a few key motivations.

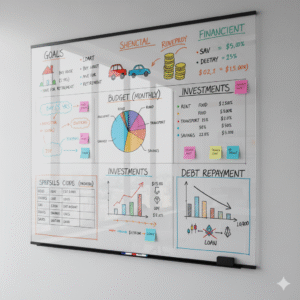

1. To Raise Massive Amounts of Capital

This is the number one reason. An IPO is a massive fundraising event. By selling shares to the public, a company can raise billions of dollars in a single day. This cash isn’t a loan; it doesn’t need to be paid back. The company can use this capital to:

- Fund research and development (R&D) for new products.

- Expand into new markets or countries.

- Build new factories or data centers.

- Pay down existing debt.

- Acquire other, smaller companies.

2. To “Cash Out” Early Investors (Provide Liquidity)

Imagine you’re an early employee who was paid in stock options, or a venture capitalist who invested $10 million a decade ago. Your “on-paper” wealth is massive, but you can’t spend it. You own a piece of a private company, but there’s no easy way to sell it. This is called being “illiquid.”

An IPO provides the liquidity everyone has been waiting for. It creates a public market where founders, employees, and early investors can finally sell their shares (usually after a “lock-up period,” which we’ll discuss later) and turn their paper wealth into actual cash.

3. To Gain Prestige and Public Awareness

Going public is the “big league” of business. Having your company’s ticker symbol scroll across the bottom of CNBC or Bloomberg is a huge marketing and branding boost. It signals to the world that your company has reached a certain level of scale and maturity. This prestige can make it easier to attract top talent (who are excited by public stock options) and build trust with large corporate customers.

4. To Create a “Currency” for Acquisitions

When a public company wants to buy another company, it doesn’t always have to pay in cash. It can use its own stock as a form of currency. A publicly-traded stock has a clear, real-time value, making it an attractive form of payment for the company being acquired.

The Journey to IPO Day: A Step-by-Step Process

Going public isn’t a simple decision. It’s a grueling, 6-to-12-month (or longer) process that involves a small army of bankers, lawyers, and accountants.

Step 1: Hire the Underwriters (The “Beauty Contest”)

A company can’t go public on its own. It needs to hire investment banks (like Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, or JPMorgan Chase) to manage the entire process. These banks are called the “underwriters.”

Choosing the lead underwriter is a high-stakes “beauty contest.” The company’s executives listen to pitches from all the top banks, who all promise they can get the company the best valuation and stock price.

Step 2: The SEC Filing: What Is the S-1 Prospectus?

This is the most critical document. The company and its underwriters prepare a massive registration statement, called the S-1 Prospectus, to file with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

The S-1 is the company’s “tell-all” book. It must legally disclose everything an investor would need to know to make an informed decision. This includes:

- The company’s full business model and history.

- Detailed financial statements (revenue, profit, loss, debt).

- A list of all the major “risk factors” (e.g., “We have never been profitable,” “We rely on one main supplier,” “Our CEO is in a lawsuit”).

- Who the main executives and shareholders are.

- What the company plans to do with the IPO money.

The SEC reviews the S-1 and can send back comments and questions, forcing the company to revise and refile it multiple times.

Step 3: The “Quiet Period” and the “Roadshow”

Once the S-1 is filed, the company enters a “quiet period.” During this time, the SEC severely restricts what the company and its executives can say in public. They can’t hype the stock or make new, forward-looking promises that aren’t in the S-1, as this could unfairly influence investors.

Meanwhile, the executives and bankers go on a “roadshow.” This is a whirlwind, multi-city tour where they present to large institutional investors (like hedge funds and mutual funds) to build excitement and gauge demand. They try to “build the book” of orders from these big players.

Step 4: Pricing the IPO (The Offering Price)

The night before the IPO, the company and its underwriters get together to set the final “offering price.” This is the price at which they will sell the initial shares to those big investors.

This is a delicate art.

- Price it too high, and investors might not buy, leading to a “broken IPO” where the stock falls on day one.

- Price it too low, and the company “leaves money on the table,” giving up millions in capital it could have raised.

Step 5: “IPO Day”: The Stock Hits the Market

This is the big day. The company’s CEO rings the opening bell at the NYSE or NASDAQ. The initial shares, sold at the “offering price,” are delivered to the institutional investors.

Then, a few hours after the market opens, the stock begins trading publicly under its new ticker symbol. This is the first time regular investors can buy the stock. The price you see on your screen is not the offering price; it’s the “first trade” price, which is determined by the supply and demand in the open market.

The Pros and Cons of Going Public: A Balanced View

Going public is a life-changing event for a company, but it’s not all good news. It’s a permanent, two-sided trade-off.

The Advantages (Pros)

- Massive Capital: As discussed, access to billions of dollars in funding.

- Public Currency: Stock can be used for acquisitions.

- Liquidity: Founders and employees can finally sell their shares.

- Prestige: Boosts brand awareness and credibility.

- Attracting Talent: Publicly-traded stock options (RSUs) are a powerful recruiting tool.

The Disadvantages (Cons)

- Extreme Cost: An IPO is incredibly expensive. Legal, accounting, and banking fees can easily run into the millions, or tens of millions, of dollars.

- Loss of Control: The founder, who was once king, now has a board of directors, shareholders, and activists to answer to. They can even be voted out of their own company.

- Intense Public Scrutiny: The company must now report its financial results every three months (in 10-Q and 10-K filings). Every move is analyzed by Wall Street.

- Short-Term Pressure: This is a major complaint. Public shareholders often demand strong quarterly profits. This can force executives to focus on short-term results at the expense of long-term innovation.

- Disclosure of Secrets: The S-1 and quarterly filings force the company to reveal information that their private competitors would love to know.

How Can a Regular Investor Buy IPO Shares?

This is a common and confusing question. For decades, “getting in on the IPO price” was a privilege reserved only for the wealthiest clients of the big investment banks. The offering price was not available to the public.

By the time you, the retail investor, could buy the stock on IPO day, the price had often already “popped” 20%, 50%, or 100%. You were buying from the institutional investors who were already cashing in.

This has changed recently.

- Modern Brokerages: Platforms like Robinhood and SoFi have struck deals with underwriters to reserve a small allotment of IPO shares for their retail customers at the offering price. Access is still limited and often allocated via a lottery system, but it is now possible for regular investors to participate.

- Directed Share Programs: Sometimes, a company will reserve a portion of its IPO shares for its own customers or employees.

For most people, however, buying an IPO still means buying it on the open market after it has started trading, which carries all the risks of buying a highly-volatile, newly-listed stock.

The Major Risks of Investing in IPOs (Buyer Beware!)

The idea of “getting in on the ground floor” of the next Google is intoxicating. But the reality is that investing in IPOs is one of the riskiest activities in the stock market.

1. The Hype vs. The Fundamentals

IPOs are marketing events. They are designed by bankers to be as exciting as possible to get the highest price. Often, investors get caught in the hype and buy a stock based on a “good story” rather than its actual financial health. Many IPO companies are unprofitable, and their S-1 documents clearly state they may never be profitable. The dot-com bubble of 1999-2000 was built on hyped-up, unprofitable IPOs that ultimately went to zero.

2. Extreme Volatility

New stocks are notoriously volatile. With no trading history, the market struggles to find a “fair” price. It’s not uncommon to see a new stock swing 10-15% in a single day. You must have a strong stomach for risk.

3. The “IPO Pop” Can Be a Trap

That famous “IPO pop” (the surge in price on the first day) is often driven by scarcity. Underwriters may intentionally underprice the offering and release a limited number of shares to create a first-day buying frenzy. Many investors who chase this pop and buy at the high of the first day find themselves holding a stock that slowly bleeds value over the next few months as the hype fades.

4. The Lock-Up Period Expiration

This is the most important risk to understand.

- A lock-up period is a contractual agreement that prevents company insiders (founders, employees, venture capitalists) from selling their shares for a set period, typically 90 to 180 days after the IPO.

- What happens when that period ends? A massive “supply” of new shares is suddenly eligible to be sold on the market.

- If all these insiders rush to cash out, it can flood the market and cause the stock price to drop significantly. Always know when an IPO’s lock-up period expires.

IPO vs. Direct Listing vs. SPACs: What’s the Difference?

The traditional IPO isn’t the only way to go public anymore. In recent years, two other methods have become popular.

- Direct Listing (DL): Pioneered by companies like Spotify and Slack. In a direct listing, the company does not hire underwriters and does not raise any new capital. It simply lists its existing shares (owned by employees and insiders) on an exchange and lets them start trading. It’s cheaper and avoids the lock-up period, but it doesn’t raise any money for the company.

- SPAC: This stands for Special Purpose Acquisition Company. A SPAC is a “blank check” company. It’s a shell company that has no actual business operations. It goes public through an IPO first, with the sole purpose of raising capital to then go out and acquire a private company later. For the private company, merging with a SPAC is a faster, easier way to “go public” than a traditional IPO.

Is Investing in an IPO a Good Idea?

An IPO is a critical event that fuels innovation and builds wealth. But for the average investor, it’s rarely a “get rich quick” ticket. It’s a high-risk speculation.

A smart investor doesn’t buy a stock just because it’s a “hot IPO.” A smart investor waits for the hype to die down, reads the company’s financial reports (the S-1, 10-Q, and 10-K), and makes a decision based on the business’s long-term fundamentals, not its first-day pop.